Exploratory data analysis and quality control

Last updated on 2024-11-11 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 45 minutes

Overview

Questions

- How do I examine the quality of single-cell data?

- What data visualizations should I use during quality control in a single-cell analysis?

- How do I prepare single-cell data for analysis?

Objectives

- Determine and communicate the quality of single-cell data.

- Identify and filter empty droplets and doublets.

- Perform normalization, feature selection, and dimensionality reduction as parts of a typical single-cell analysis pipeline.

Setup and experimental design

As mentioned in the introduction, in this tutorial we will use the wild-type data from the Tal1 chimera experiment. These data are available through the MouseGastrulationData Bioconductor package, which contains several datasets.

In particular, the package contains the following samples that we will use for the tutorial:

- Sample 5: E8.5 injected cells (tomato positive), pool 3

- Sample 6: E8.5 host cells (tomato negative), pool 3

- Sample 7: E8.5 injected cells (tomato positive), pool 4

- Sample 8: E8.5 host cells (tomato negative), pool 4

- Sample 9: E8.5 injected cells (tomato positive), pool 5

- Sample 10: E8.5 host cells (tomato negative), pool 5

We start our analysis by selecting only sample 5, which contains the injected cells in one biological replicate. We download the “raw” data that contains all the droplets for which we have sequenced reads.

R

library(MouseGastrulationData)

library(DropletUtils)

library(ggplot2)

library(EnsDb.Mmusculus.v79)

library(scuttle)

library(scater)

library(scran)

library(scDblFinder)

sce <- WTChimeraData(samples = 5, type = "raw")

sce <- sce[[1]]

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 522554

metadata(0):

assays(1): counts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(522554): AAACCTGAGAAACCAT AAACCTGAGAAACCGC ...

TTTGTCATCTTTACGT TTTGTCATCTTTCCTC

colData names(0):

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):This is the same data we examined in the previous lesson.

Droplet processing

From the experiment, we expect to have only a few thousand cells, while we can see that we have data for more than 500,000 droplets. It is likely that most of these droplets are empty and are capturing only ambient or background RNA.

Callout

Depending on your data source, identifying and discarding empty droplets may not be necessary. Some academic institutions have research cores dedicated to single cell work that perform the sample preparation and sequencing. Many of these cores will also perform empty droplet filtering and other initial QC steps. Specific details on the steps in common pipelines like 10x Genomics’ CellRanger can usually be found in the documentation that came with the sequencing material.

The main point is: if the sequencing outputs were provided to you by someone else, make sure to communicate with them about what pre-processing steps have been performed, if any.

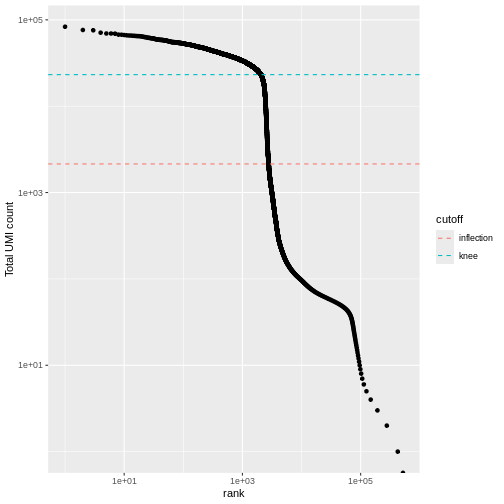

We can visualize barcode read totals to visualize the distinction between empty droplets and properly profiled single cells in a so-called “knee plot”:

R

bcrank <- barcodeRanks(counts(sce))

# Only showing unique points for plotting speed.

uniq <- !duplicated(bcrank$rank)

line_df <- data.frame(cutoff = names(metadata(bcrank)),

value = unlist(metadata(bcrank)))

ggplot(bcrank[uniq,], aes(rank, total)) +

geom_point() +

geom_hline(data = line_df,

aes(color = cutoff,

yintercept = value),

lty = 2) +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10() +

labs(y = "Total UMI count")

The distribution of total counts (called the unique molecular identifier or UMI count) exhibits a sharp transition between barcodes with large and small total counts, probably corresponding to cell-containing and empty droplets respectively.

A simple approach would be to apply a threshold on the total count to only retain those barcodes with large totals. However, this may unnecessarily discard libraries derived from cell types with low RNA content.

Challenge

What is the median number of total counts in the raw data?

R

median(bcrank$total)

OUTPUT

[1] 2Just 2! Clearly many barcodes produce practically no output.

Testing for empty droplets

A better approach is to test whether the expression profile for each cell barcode is significantly different from the ambient RNA pool1. Any significant deviation indicates that the barcode corresponds to a cell-containing droplet. This allows us to discriminate between well-sequenced empty droplets and droplets derived from cells with little RNA, both of which would have similar total counts.

We call cells at a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.1%, meaning that no more than 0.1% of our called barcodes should be empty droplets on average.

R

# emptyDrops performs Monte Carlo simulations to compute p-values,

# so we need to set the seed to obtain reproducible results.

set.seed(100)

# this may take a few minutes

e.out <- emptyDrops(counts(sce))

summary(e.out$FDR <= 0.001)

OUTPUT

Mode FALSE TRUE NA's

logical 6184 3131 513239 R

sce <- sce[,which(e.out$FDR <= 0.001)]

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 3131

metadata(0):

assays(1): counts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(3131): AAACCTGAGACTGTAA AAACCTGAGATGCCTT ... TTTGTCAGTCTGATTG

TTTGTCATCTGAGTGT

colData names(0):

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):The result confirms our expectation: only 3,131 droplets contain a cell, while the large majority of droplets are empty.

Whenever your code involves the generation of random numbers, it’s a

good practice to set the random seed in R with

set.seed().

Setting the seed to a specific value (in the above example to 100) will cause the pseudo-random number generator to return the same pseudo-random numbers in the same order.

This allows us to write code with reproducible results, despite technically involving the generation of (pseudo-)random numbers.

Quality control

While we have removed empty droplets, this does not necessarily imply that all the cell-containing droplets should be kept for downstream analysis. In fact, some droplets could contain low-quality samples, due to cell damage or failure in library preparation.

Retaining these low-quality samples in the analysis could be problematic as they could:

- form their own cluster, complicating the interpretation of the results

- interfere with variance estimation and principal component analysis

- contain contaminating transcripts from ambient RNA

To mitigate these problems, we can check a few quality control (QC) metrics and, if needed, remove low-quality samples.

Choice of quality control metrics

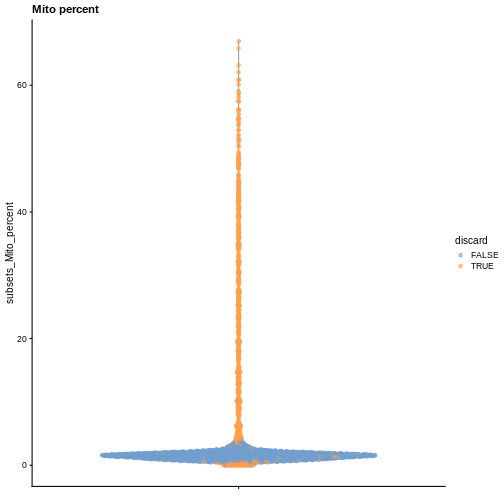

There are many possible ways to define a set of quality control metrics, see for instance Cole 2019. Here, we keep it simple and consider only:

- the library size, defined as the total sum of counts across all relevant features for each cell;

- the number of expressed features in each cell, defined as the number of endogenous genes with non-zero counts for that cell;

- the proportion of reads mapped to genes in the mitochondrial genome.

In particular, high proportions of mitochondrial genes are indicative of poor-quality cells, presumably because of loss of cytoplasmic RNA from perforated cells. The reasoning is that, in the presence of modest damage, the holes in the cell membrane permit efflux of individual transcript molecules but are too small to allow mitochondria to escape, leading to a relative enrichment of mitochondrial transcripts. For single-nucleus RNA-seq experiments, high proportions are also useful as they can mark cells where the cytoplasm has not been successfully stripped.

First, we need to identify mitochondrial genes. We use the available

EnsDb mouse package available in Bioconductor, but a more

updated version of Ensembl can be used through the

AnnotationHub or biomaRt packages.

R

chr.loc <- mapIds(EnsDb.Mmusculus.v79,

keys = rownames(sce),

keytype = "GENEID",

column = "SEQNAME")

is.mito <- which(chr.loc == "MT")

We can use the scuttle package to compute a set of

quality control metrics, specifying that we want to use the

mitochondrial genes as a special set of features.

R

df <- perCellQCMetrics(sce, subsets = list(Mito = is.mito))

colData(sce) <- cbind(colData(sce), df)

colData(sce)

OUTPUT

DataFrame with 3131 rows and 6 columns

sum detected subsets_Mito_sum subsets_Mito_detected

<numeric> <integer> <numeric> <integer>

AAACCTGAGACTGTAA 27577 5418 471 10

AAACCTGAGATGCCTT 29309 5405 679 10

AAACCTGAGCAGCCTC 28795 5218 480 12

AAACCTGCATACTCTT 34794 4781 496 12

AAACCTGGTGGTACAG 262 229 0 0

... ... ... ... ...

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA 38398 6020 252 12

TTTGTCACACCCTATC 3013 1451 123 9

TTTGTCACATTCTCAT 1472 675 599 11

TTTGTCAGTCTGATTG 361 293 0 0

TTTGTCATCTGAGTGT 267 233 16 6

subsets_Mito_percent total

<numeric> <numeric>

AAACCTGAGACTGTAA 1.70795 27577

AAACCTGAGATGCCTT 2.31669 29309

AAACCTGAGCAGCCTC 1.66696 28795

AAACCTGCATACTCTT 1.42553 34794

AAACCTGGTGGTACAG 0.00000 262

... ... ...

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA 0.656284 38398

TTTGTCACACCCTATC 4.082310 3013

TTTGTCACATTCTCAT 40.692935 1472

TTTGTCAGTCTGATTG 0.000000 361

TTTGTCATCTGAGTGT 5.992509 267Now that we have computed the metrics, we have to decide on thresholds to define high- and low-quality samples. We could check how many cells are above/below a certain fixed threshold. For instance,

R

table(df$sum < 10000)

OUTPUT

FALSE TRUE

2477 654 R

table(df$subsets_Mito_percent > 10)

OUTPUT

FALSE TRUE

2761 370 or we could look at the distribution of such metrics and use a data adaptive threshold.

R

summary(df$detected)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

98 4126 5168 4455 5670 7908 R

summary(df$subsets_Mito_percent)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.000 1.155 1.608 5.079 2.182 66.968 We can use the perCellQCFilters function to apply a set

of common adaptive filters to identify low-quality cells. By default, we

consider a value to be an outlier if it is more than 3 median absolute

deviations (MADs) from the median in the “problematic” direction. This

is loosely motivated by the fact that such a filter will retain 99% of

non-outlier values that follow a normal distribution.

R

reasons <- perCellQCFilters(df, sub.fields = "subsets_Mito_percent")

reasons

OUTPUT

DataFrame with 3131 rows and 4 columns

low_lib_size low_n_features high_subsets_Mito_percent discard

<outlier.filter> <outlier.filter> <outlier.filter> <logical>

1 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

2 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

3 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

4 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

5 TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE

... ... ... ... ...

3127 FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE

3128 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE

3129 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE

3130 TRUE TRUE FALSE TRUE

3131 TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUER

sce$discard <- reasons$discard

Challenge

Maybe our sample preparation was poor and we want the QC to be more strict. How could we change the set the QC filtering to use 2.5 MADs as the threshold for outlier calling?

You set nmads = 2.5 like so:

R

reasons_strict <- perCellQCFilters(df, sub.fields = "subsets_Mito_percent", nmads = 2.5)

You would then need to reassign the discard column as

well, but we’ll stick with the 3 MADs default for now.

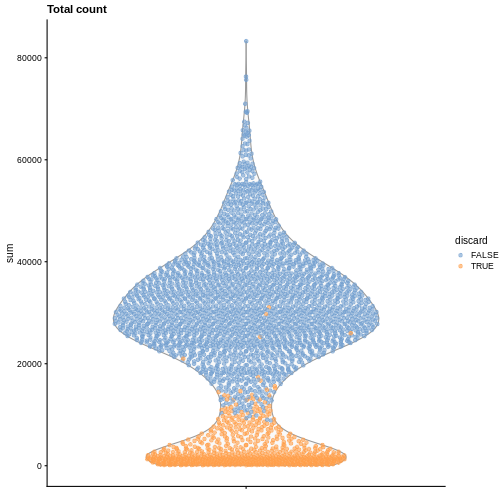

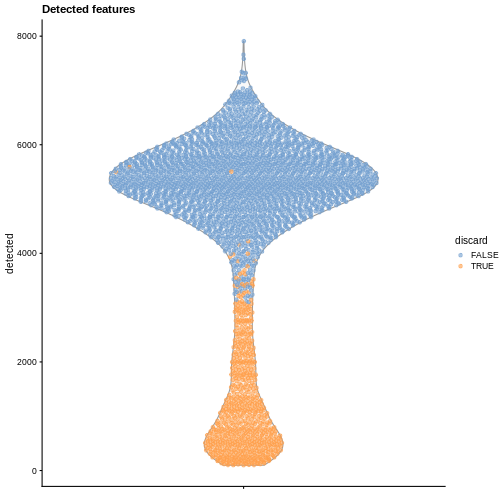

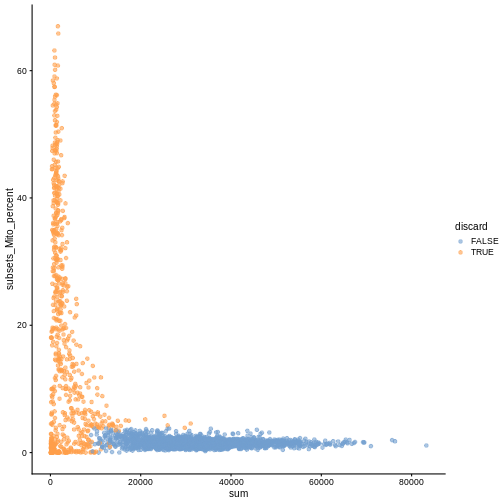

Diagnostic plots

It is always a good idea to check the distribution of the QC metrics and to visualize the cells that were removed, to identify possible problems with the procedure. In particular, we expect to have few outliers and with a marked difference from “regular” cells (e.g., a bimodal distribution or a long tail). Moreover, if there are too many discarded cells, further exploration might be needed.

R

plotColData(sce, y = "sum", colour_by = "discard") +

labs(title = "Total count")

R

plotColData(sce, y = "detected", colour_by = "discard") +

labs(title = "Detected features")

R

plotColData(sce, y = "subsets_Mito_percent", colour_by = "discard") +

labs(title = "Mito percent")

While the univariate distribution of QC metrics can give some insight on the quality of the sample, often looking at the bivariate distribution of QC metrics is useful, e.g., to confirm that there are no cells with both large total counts and large mitochondrial counts, to ensure that we are not inadvertently removing high-quality cells that happen to be highly metabolically active.

R

plotColData(sce, x ="sum", y = "subsets_Mito_percent", colour_by = "discard")

It could also be a good idea to perform a differential expression analysis between retained and discarded cells to check wether we are removing an unusual cell population rather than low-quality libraries (see Section 1.5 of OSCA advanced).

Once we are happy with the results, we can discard the low-quality cells by subsetting the original object.

R

sce <- sce[,!sce$discard]

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 2437

metadata(0):

assays(1): counts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(2437): AAACCTGAGACTGTAA AAACCTGAGATGCCTT ... TTTGGTTTCAGTCAGT

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA

colData names(7): sum detected ... total discard

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):Normalization

Systematic differences in sequencing coverage between libraries are often observed in single-cell RNA sequencing data. They typically arise from technical differences in cDNA capture or PCR amplification efficiency across cells, attributable to the difficulty of achieving consistent library preparation with minimal starting material2. Normalization aims to remove these differences such that they do not interfere with comparisons of the expression profiles between cells. The hope is that the observed heterogeneity or differential expression within the cell population are driven by biology and not technical biases.

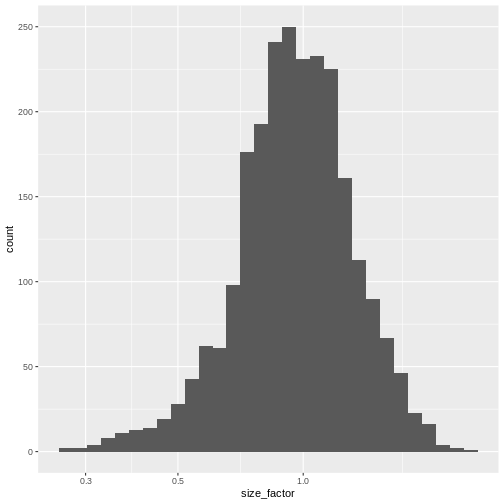

We will mostly focus our attention on scaling normalization, which is the simplest and most commonly used class of normalization strategies. This involves dividing all counts for each cell by a cell-specific scaling factor, often called a size factor. The assumption here is that any cell-specific bias (e.g., in capture or amplification efficiency) affects all genes equally via scaling of the expected mean count for that cell. The size factor for each cell represents the estimate of the relative bias in that cell, so division of its counts by its size factor should remove that bias. The resulting “normalized expression values” can then be used for downstream analyses such as clustering and dimensionality reduction.

The simplest and most natural strategy would be to normalize by the total sum of counts across all genes for each cell. This is often called the library size normalization.

The library size factor for each cell is directly proportional to its library size where the proportionality constant is defined such that the mean size factor across all cells is equal to 1. This ensures that the normalized expression values are on the same scale as the original counts.

R

lib.sf <- librarySizeFactors(sce)

summary(lib.sf)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.2730 0.7879 0.9600 1.0000 1.1730 2.5598 R

sf_df <- data.frame(size_factor = lib.sf)

ggplot(sf_df, aes(size_factor)) +

geom_histogram() +

scale_x_log10()

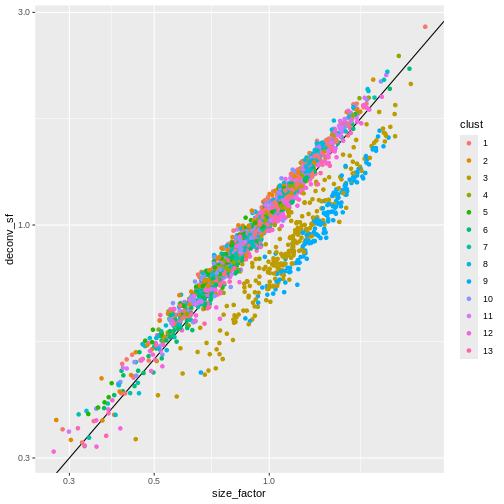

Normalization by deconvolution

Library size normalization is not optimal, as it assumes that the total sum of UMI counts differ between cells only for technical and not biological reasons. This can be a problem if a highly-expressed subset of genes is differentially expressed between cells or cell types.

Several robust normalization methods have been proposed for bulk RNA-seq. However, these methods may underperform in single-cell data due to the dominance of low and zero counts. To overcome this, one solution is to pool counts from many cells to increase the size of the counts for accurate size factor estimation3. Pool-based size factors are then deconvolved into cell-based factors for normalization of each cell’s expression profile.

We use a pre-clustering step: cells in each cluster are normalized separately and the size factors are rescaled to be comparable across clusters. This avoids the assumption that most genes are non-DE across the entire population – only a non-DE majority is required between pairs of clusters, which is a weaker assumption for highly heterogeneous populations.

Note that while we focus on normalization by deconvolution here, many other methods have been proposed and lead to similar performance (see Borella 2022 for a comparative review).

R

set.seed(100)

clust <- quickCluster(sce)

table(clust)

OUTPUT

clust

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

273 159 250 122 187 201 154 252 152 169 199 215 104 R

deconv.sf <- pooledSizeFactors(sce, cluster = clust)

summary(deconv.sf)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.3100 0.8028 0.9626 1.0000 1.1736 2.7858 R

sf_df$deconv_sf <- deconv.sf

sf_df$clust <- clust

ggplot(sf_df, aes(size_factor, deconv_sf)) +

geom_abline() +

geom_point(aes(color = clust)) +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10()

Once we have computed the size factors, we compute the normalized

expression values for each cell by dividing the count for each gene with

the appropriate size factor for that cell. Since we are typically going

to work with log-transformed counts, the function

logNormCounts also log-transforms the normalized values,

creating a new assay called logcounts.

R

sizeFactors(sce) <- deconv.sf

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 2437

metadata(0):

assays(2): counts logcounts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(2437): AAACCTGAGACTGTAA AAACCTGAGATGCCTT ... TTTGGTTTCAGTCAGT

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA

colData names(8): sum detected ... discard sizeFactor

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):R

lib.sf <- librarySizeFactors(sce)

sizeFactors(sce) <- lib.sf

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

sce

If you run this chunk, make sure to go back and re-run the normalization with deconvolution normalization if you want your work to align with the rest of this episode.

Feature Selection

The typical next steps in the analysis of single-cell data are dimensionality reduction and clustering, which involve measuring the similarity between cells.

The choice of genes to use in this calculation has a major impact on the results. We want to select genes that contain useful information about the biology of the system while removing genes that contain only random noise. This aims to preserve interesting biological structure without the variance that obscures that structure, and to reduce the size of the data to improve computational efficiency of later steps.

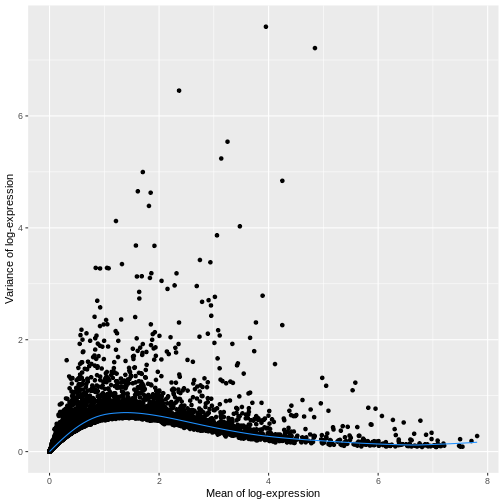

Quantifying per-gene variation

The simplest approach to feature selection is to select the most variable genes based on their log-normalized expression across the population. This is motivated by practical idea that if we’re going to try to explain variation in gene expression by biological factors, those genes need to have variance to explain.

Calculation of the per-gene variance is simple but feature selection

requires modeling of the mean-variance relationship. The

log-transformation is not a variance stabilizing transformation in most

cases, which means that the total variance of a gene is driven more by

its abundance than its underlying biological heterogeneity. To account

for this, the modelGeneVar function fits a trend to the

variance with respect to abundance across all genes.

R

dec.sce <- modelGeneVar(sce)

fit.sce <- metadata(dec.sce)

mean_var_df <- data.frame(mean = fit.sce$mean,

var = fit.sce$var)

ggplot(mean_var_df, aes(mean, var)) +

geom_point() +

geom_function(fun = fit.sce$trend,

color = "dodgerblue") +

labs(x = "Mean of log-expression",

y = "Variance of log-expression")

The blue line represents the uninteresting “technical” variance for any given gene abundance. The genes with a lot of additional variance exhibit interesting “biological” variation.

Selecting highly variable genes

The next step is to select the subset of HVGs to use in downstream

analyses. A larger set will assure that we do not remove important

genes, at the cost of potentially increasing noise. Typically, we

restrict ourselves to the top \(n\)

genes, here we chose \(n = 1000\), but

this choice should be guided by prior biological knowledge; for

instance, we may expect that only about 10% of genes to be

differentially expressed across our cell populations and hence select

10% of genes as highly variable (e.g., by setting

prop = 0.1).

R

hvg.sce.var <- getTopHVGs(dec.sce, n = 1000)

head(hvg.sce.var)

OUTPUT

[1] "ENSMUSG00000055609" "ENSMUSG00000052217" "ENSMUSG00000069919"

[4] "ENSMUSG00000052187" "ENSMUSG00000048583" "ENSMUSG00000051855"Challenge

Imagine you have data that were prepared by three people with varying level of experience, which leads to varying technical noise. How can you account for this blocking structure when selecting HVGs?

modelGeneVar() can take a block

argument.

Use the block argument in the call to

modelGeneVar() like so. We don’t have experimenter

information in this dataset, so in order to have some names to work with

we assign them randomly from a set of names.

R

sce$experimenter = factor(sample(c("Perry", "Merry", "Gary"),

replace = TRUE,

size = ncol(sce)))

blocked_variance_df = modelGeneVar(sce,

block = sce$experimenter)

Blocked models are evaluated on each block separately then combined.

If the experimental groups are related in some structured way, it may be

preferable to use the design argument. See

?modelGeneVar for more detail.

Dimensionality Reduction

Many scRNA-seq analysis procedures involve comparing cells based on their expression values across multiple genes. For example, clustering aims to identify cells with similar transcriptomic profiles by computing Euclidean distances across genes. In these applications, each individual gene represents a dimension of the data, hence we can think of the data as “living” in a ten-thousand-dimensional space.

As the name suggests, dimensionality reduction aims to reduce the number of dimensions, while preserving as much as possible of the original information. This obviously reduces the computational work (e.g., it is easier to compute distance in lower-dimensional spaces), and more importantly leads to less noisy and more interpretable results (cf. the curse of dimensionality).

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a dimensionality reduction technique that provides a parsimonious summarization of the data by replacing the original variables (genes) by fewer linear combinations of these variables, that are orthogonal and have successively maximal variance. Such linear combinations seek to “separate out” the observations (cells), while losing as little information as possible.

Without getting into the technical details, one nice feature of PCA is that the principal components (PCs) are ordered by how much variance of the original data they “explain”. Furthermore, by focusing on the top \(k\) PC we are focusing on the most important directions of variability, which hopefully correspond to biological rather than technical variance. (It is however good practice to check this by e.g. looking at correlation between technical QC metrics and PCs).

One simple way to maximize our chance of capturing biological variation is by computing the PCs starting from the highly variable genes identified before.

R

sce <- runPCA(sce, subset_row = hvg.sce.var)

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 2437

metadata(0):

assays(2): counts logcounts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(2437): AAACCTGAGACTGTAA AAACCTGAGATGCCTT ... TTTGGTTTCAGTCAGT

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA

colData names(8): sum detected ... discard sizeFactor

reducedDimNames(1): PCA

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):By default, runPCA computes the first 50 principal

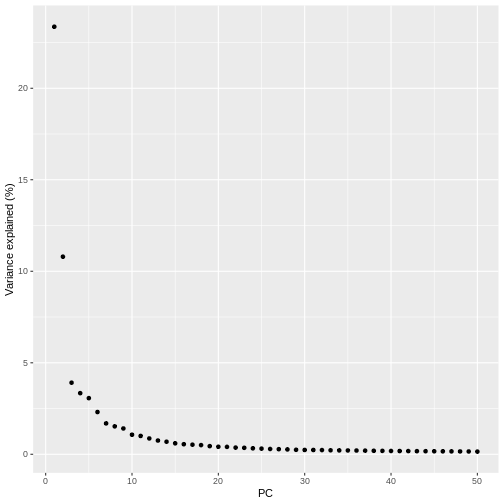

components. We can check how much original variability they explain.

These values are stored in the attributes of the percentVar

reducedDim:

R

pct_var_df <- data.frame(PC = 1:50,

pct_var = attr(reducedDim(sce), "percentVar"))

ggplot(pct_var_df,

aes(PC, pct_var)) +

geom_point() +

labs(y = "Variance explained (%)")

You can see the first two PCs capture the largest amount of variation, but in this case you have to take the first 8 PCs before you’ve captured 50% of the total.

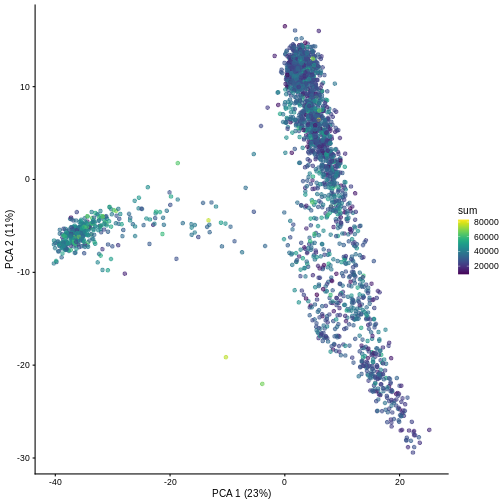

And we can of course visualize the first 2-3 components, perhaps color-coding each point by an interesting feature, in this case the total number of UMIs per cell.

R

plotPCA(sce, colour_by = "sum")

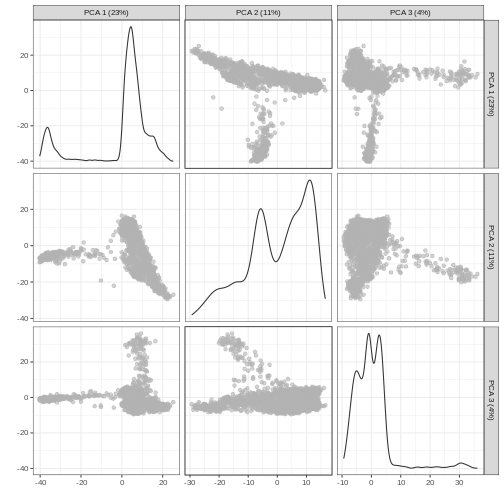

It can be helpful to compare pairs of PCs. This can be done with the

ncomponents argument to plotReducedDim(). For

example if one batch or cell type splits off on a particular PC, this

can help visualize the effect of that.

R

plotReducedDim(sce, dimred = "PCA", ncomponents = 3)

Non-linear methods

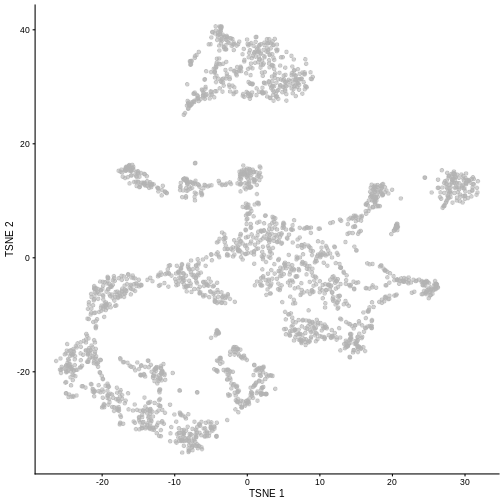

While PCA is a simple and effective way to visualize (and interpret!) scRNA-seq data, non-linear methods such as t-SNE (t-stochastic neighbor embedding) and UMAP (uniform manifold approximation and projection) have gained much popularity in the literature.

These methods attempt to find a low-dimensional representation of the data that attempt to preserve pair-wise distance and structure in high-dimensional gene space as best as possible.

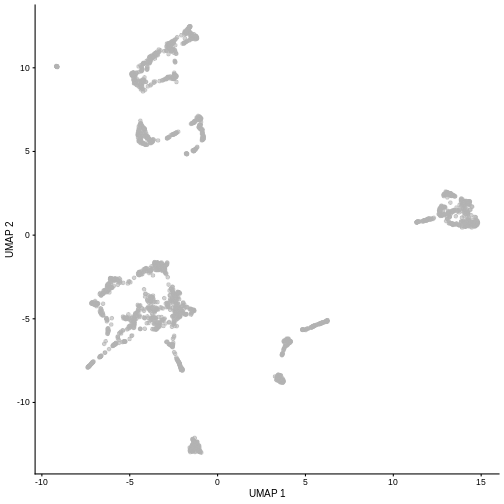

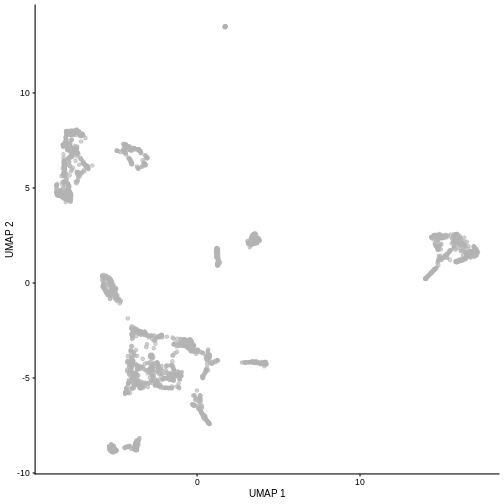

R

set.seed(100)

sce <- runTSNE(sce, dimred = "PCA")

plotTSNE(sce)

R

set.seed(111)

sce <- runUMAP(sce, dimred = "PCA")

plotUMAP(sce)

It is easy to over-interpret t-SNE and UMAP plots. We note that the relative sizes and positions of the visual clusters may be misleading, as they tend to inflate dense clusters and compress sparse ones, such that we cannot use the size as a measure of subpopulation heterogeneity.

In addition, these methods are not guaranteed to preserve the global structure of the data (e.g., the relative locations of non-neighboring clusters), such that we cannot use their positions to determine relationships between distant clusters.

Note that the sce object now includes all the computed

dimensionality reduced representations of the data for ease of reusing

and replotting without the need for recomputing. Note the added

reducedDimNames row when printing sce

here:

R

sce

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 29453 2437

metadata(0):

assays(2): counts logcounts

rownames(29453): ENSMUSG00000051951 ENSMUSG00000089699 ...

ENSMUSG00000095742 tomato-td

rowData names(2): ENSEMBL SYMBOL

colnames(2437): AAACCTGAGACTGTAA AAACCTGAGATGCCTT ... TTTGGTTTCAGTCAGT

TTTGGTTTCGCCATAA

colData names(8): sum detected ... discard sizeFactor

reducedDimNames(3): PCA TSNE UMAP

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):Despite their shortcomings, t-SNE and UMAP can be useful visualization techniques. When using them, it is important to consider that they are stochastic methods that involve a random component (each run will lead to different plots) and that there are key parameters to be set that change the results substantially (e.g., the “perplexity” parameter of t-SNE).

Challenge

Re-run the UMAP for the same sample starting from the pre-processed

data (i.e. not type = "raw"). What looks the same? What

looks different?

R

set.seed(111)

sce5 <- WTChimeraData(samples = 5)

sce5 <- logNormCounts(sce5)

sce5 <- runPCA(sce5)

sce5 <- runUMAP(sce5)

plotUMAP(sce5)

Given that it’s the same cells processed through a very similar pipeline, the result should look very similar. There’s a slight difference in the total number of cells, probably because the official processing pipeline didn’t use the exact same random seed / QC arguments as us.

But you’ll notice that even though the shape of the structures are similar, they look slightly distorted. If the upstream QC parameters change, the downstream output visualizations will also change.

Doublet identification

Doublets are artifactual libraries generated from two cells. They typically arise due to errors in cell sorting or capture. Specifically, in droplet-based protocols, it may happen that two cells are captured in the same droplet.

Doublets are obviously undesirable when the aim is to characterize populations at the single-cell level. In particular, doublets can be mistaken for intermediate populations or transitory states that do not actually exist. Thus, it is desirable to identify and remove doublet libraries so that they do not compromise interpretation of the results.

It is not easy to computationally identify doublets as they can be hard to distinguish from transient states and/or cell populations with high RNA content. When possible, it is good to rely on experimental strategies to minimize doublets, e.g., by using genetic variation (e.g., pooling multiple donors in one run) or antibody tagging (e.g., CITE-seq).

There are several computational methods to identify doublets; we describe only one here based on in-silico simulation of doublets.

Computing doublet densities

At a high level, the algorithm can be defined by the following steps:

- Simulate thousands of doublets by adding together two randomly chosen single-cell profiles.

- For each original cell, compute the density of simulated doublets in the surrounding neighborhood.

- For each original cell, compute the density of other observed cells in the neighborhood.

- Return the ratio between the two densities as a “doublet score” for each cell.

Intuitively, if a “cell” is surrounded only by simulated doublets is very likely to be a doublet itself.

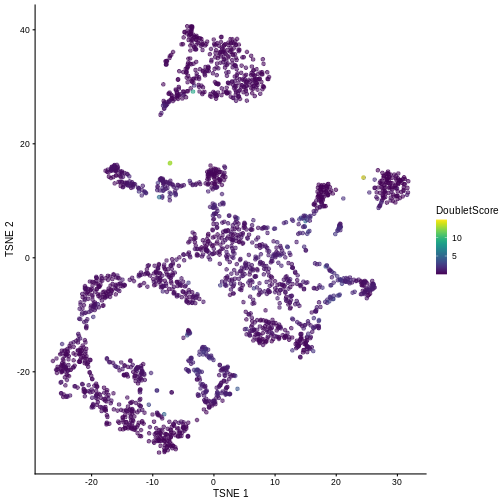

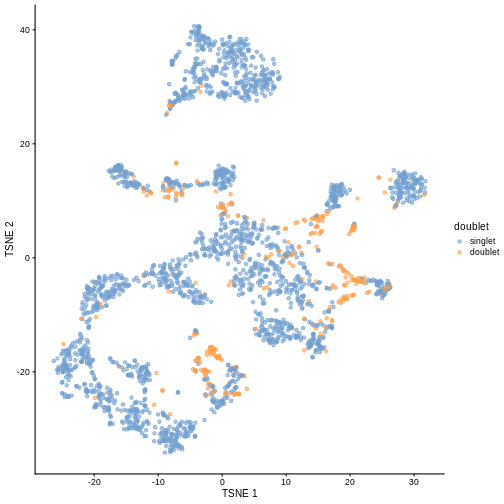

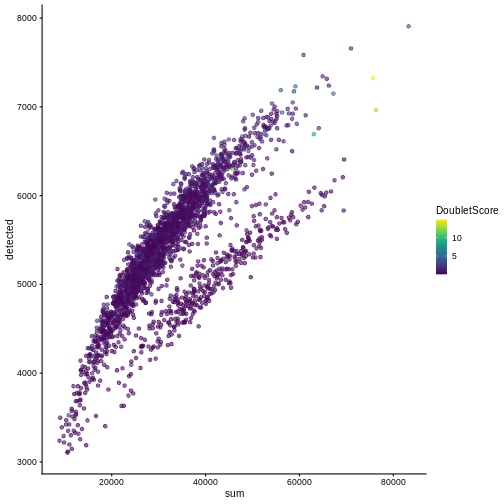

This approach is implemented below using the scDblFinder

library. We then visualize the scores in a t-SNE plot.

R

set.seed(100)

dbl.dens <- computeDoubletDensity(sce, subset.row = hvg.sce.var,

d = ncol(reducedDim(sce)))

summary(dbl.dens)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.04874 0.28757 0.46790 0.65614 0.82371 14.88032 R

sce$DoubletScore <- dbl.dens

plotTSNE(sce, colour_by = "DoubletScore")

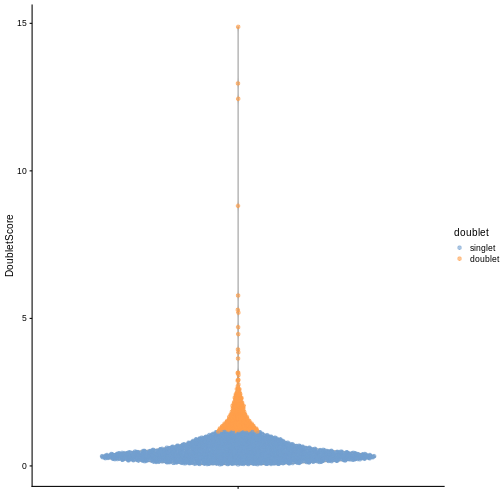

We can explicitly convert this into doublet calls by identifying large outliers for the score within each sample. Here we use the “griffiths” method to do so.

R

dbl.calls <- doubletThresholding(data.frame(score = dbl.dens),

method = "griffiths",

returnType = "call")

summary(dbl.calls)

OUTPUT

singlet doublet

2124 313 R

sce$doublet <- dbl.calls

plotColData(sce, y = "DoubletScore", colour_by = "doublet")

R

plotTSNE(sce, colour_by = "doublet")

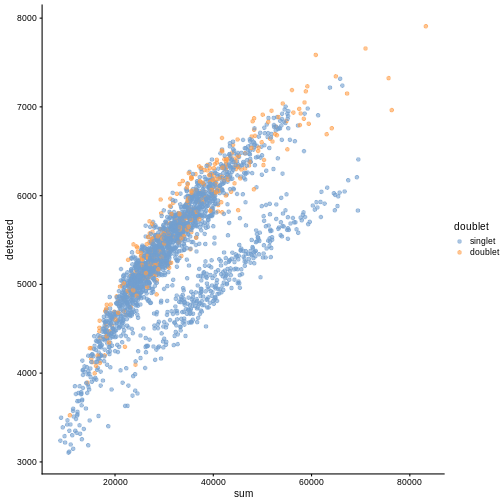

One way to determine whether a cell is in a real transient state or it is a doublet is to check the number of detected genes and total UMI counts.

R

plotColData(sce, "detected", "sum", colour_by = "DoubletScore")

R

plotColData(sce, "detected", "sum", colour_by = "doublet")

In this case, we only have a few doublets at the periphery of some clusters. It could be fine to keep the doublets in the analysis, but it may be safer to discard them to avoid biases in downstream analysis (e.g., differential expression).

Exercises

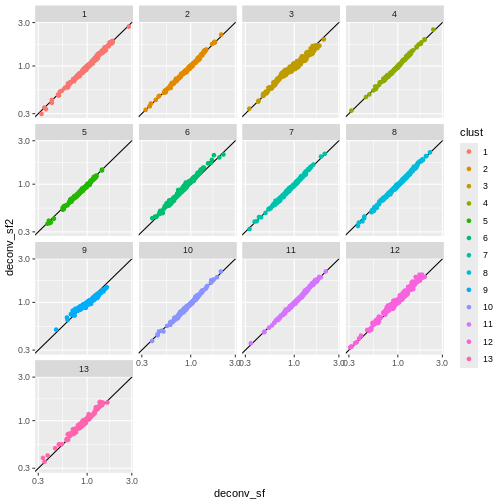

Exercise 1: Normalization

Here we used the deconvolution method implemented in

scran based on a previous clustering step. Use the

pooledSizeFactors to compute the size factors without

considering a preliminary clustering. Compare the resulting size factors

via a scatter plot. How do the results change? What are the risks of not

including clustering information?

R

deconv.sf2 <- pooledSizeFactors(sce) # dropped `cluster = clust` here

summary(deconv.sf2)

OUTPUT

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

0.2985 0.8142 0.9583 1.0000 1.1582 2.7054 R

sf_df$deconv_sf2 <- deconv.sf2

sf_df$clust <- clust

ggplot(sf_df, aes(deconv_sf, deconv_sf2)) +

geom_abline() +

geom_point(aes(color = clust)) +

scale_x_log10() +

scale_y_log10() +

facet_wrap(vars(clust))

You can see that we get largely similar results, though for clusters

3 and 9 there’s a slight deviation from the y=x

relationship because these clusters (which are fairly distinct from the

other clusters) are now being pooled with cells from other clusters.

This slightly violates the “majority non-DE genes” assumption.

Exercise 2: PBMC Data

The DropletTestFiles

package includes the raw output from Cell Ranger of the peripheral

blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) dataset from 10X Genomics, publicly

available from the 10X Genomics website. Repeat the analysis of this

vignette using those data.

The hint demonstrates how to identify, download, extract, and read

the data starting from the help documentation of

?DropletTestFiles::listTestFiles, but try working through

those steps on your own for extra challenge (they’re useful skills to

develop in practice).

R

library(DropletTestFiles)

set.seed(100)

listTestFiles(dataset = "tenx-3.1.0-5k_pbmc_protein_v3") # look up the remote data path of the raw data

raw_rdatapath <- "DropletTestFiles/tenx-3.1.0-5k_pbmc_protein_v3/1.0.0/raw.tar.gz"

local_path <- getTestFile(raw_rdatapath, prefix = FALSE)

file.copy(local_path,

paste0(local_path, ".tar.gz"))

untar(paste0(local_path, ".tar.gz"),

exdir = dirname(local_path))

sce <- read10xCounts(file.path(dirname(local_path), "raw_feature_bc_matrix/"))

After getting the data, the steps are largely copy-pasted from above. For the sake of simplicity the mitochondrial genes are identified by gene symbols in the row data. Otherwise the steps are the same:

R

e.out <- emptyDrops(counts(sce))

sce <- sce[,which(e.out$FDR <= 0.001)]

# Thankfully the data come with gene symbols, which we can use to identify mitochondrial genes:

is.mito <- grepl("^MT-", rowData(sce)$Symbol)

# QC metrics ----

df <- perCellQCMetrics(sce, subsets = list(Mito = is.mito))

colData(sce) <- cbind(colData(sce), df)

colData(sce)

reasons <- perCellQCFilters(df, sub.fields = "subsets_Mito_percent")

reasons

sce$discard <- reasons$discard

sce <- sce[,!sce$discard]

# Normalization ----

clust <- quickCluster(sce)

table(clust)

deconv.sf <- pooledSizeFactors(sce, cluster = clust)

sizeFactors(sce) <- deconv.sf

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

# Feature selection ----

dec.sce <- modelGeneVar(sce)

hvg.sce.var <- getTopHVGs(dec.sce, n = 1000)

# Dimensionality reduction ----

sce <- runPCA(sce, subset_row = hvg.sce.var)

sce <- runTSNE(sce, dimred = "PCA")

sce <- runUMAP(sce, dimred = "PCA")

# Doublet finding ----

dbl.dens <- computeDoubletDensity(sce, subset.row = hvg.sce.var,

d = ncol(reducedDim(sce)))

sce$DoubletScore <- dbl.dens

dbl.calls <- doubletThresholding(data.frame(score = dbl.dens),

method = "griffiths",

returnType = "call")

sce$doublet <- dbl.calls

Extension challenge 1: Spike-ins

Some sophisticated experiments perform additional steps so that they can estimate size factors from so-called “spike-ins”. Judging by the name, what do you think “spike-ins” are, and what additional steps are required to use them?

Spike-ins are deliberately-introduced exogeneous RNA from an exotic or synthetic source at a known concentration. This provides a known signal to normalize against. Exotic (e.g. soil bacteria RNA in a study of human cells) or synthetic RNA is used in order to avoid confusing spike-in RNA with sample RNA. This has the obvious advantage of accounting for cell-wise variation, but can substantially increase the amount of sample-preparation work.

Extension challenge 2: Background research

Run an internet search for some of the most highly variable genes we identified in the feature selection section. See if you can identify the type of protein they produce or what sort of process they’re involved in. Do they make biological sense to you?

Extension challenge 3: Reduced dimensionality representations

Can dimensionality reduction techniques provide a perfectly accurate representation of the data?

Mathematically, this would require the data to fall on a two-dimensional plane (for linear methods like PCA) or a smooth 2D manifold (for methods like UMAP). You can be confident that this will never happen in real-world data, so the reduction from ~2500-dimensional gene space to two-dimensional plot space always involves some degree of information loss.

Key Points

- Empty droplets, i.e. droplets that do not contain intact cells and

that capture only ambient or background RNA, should be removed prior to

an analysis. The

emptyDropsfunction from the DropletUtils package can be used to identify empty droplets. - Doublets, i.e. instances where two cells are captured in the same

droplet, should also be removed prior to an analysis. The

computeDoubletDensityanddoubletThresholdingfunctions from the scDblFinder package can be used to identify doublets. - Quality control (QC) uses metrics such as library size, number of expressed features, and mitochondrial read proportion, based on which low-quality cells can be detected and filtered out. Diagnostic plots of the chosen QC metrics are important to identify possible issues.

- Normalization is required to account for systematic differences in sequencing coverage between libraries and to make measurements comparable between cells. Library size normalization is the most commonly used normalization strategy, and involves dividing all counts for each cell by a cell-specific scaling factor.

- Feature selection aims at selecting genes that contain useful

information about the biology of the system while removing genes that

contain only random noise. Calculate per-gene variance with the

modelGeneVarfunction and select highly-variable genes withgetTopHVGs. - Dimensionality reduction aims at reducing the computational work and at obtaining less noisy and more interpretable results. PCA is a simple and effective linear dimensionality reduction technique that provides interpretable results for further analysis such as clustering of cells. Non-linear approaches such as UMAP and t-SNE can be useful for visualization, but the resulting representations should not be used in downstream analysis.

Further Reading

- OSCA book, Basics, Chapters 1-4

- OSCA book, Advanced, Chapters 7-8

Session Info

R

sessionInfo()

OUTPUT

R version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/blas/libblas.so.3.10.0

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/lapack/liblapack.so.3.10.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

[4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

[10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats4 stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods

[8] base

other attached packages:

[1] scDblFinder_1.18.0 scran_1.32.0

[3] scater_1.32.0 scuttle_1.14.0

[5] EnsDb.Mmusculus.v79_2.99.0 ensembldb_2.28.0

[7] AnnotationFilter_1.28.0 GenomicFeatures_1.56.0

[9] AnnotationDbi_1.66.0 ggplot2_3.5.1

[11] DropletUtils_1.24.0 MouseGastrulationData_1.18.0

[13] SpatialExperiment_1.14.0 SingleCellExperiment_1.26.0

[15] SummarizedExperiment_1.34.0 Biobase_2.64.0

[17] GenomicRanges_1.56.0 GenomeInfoDb_1.40.1

[19] IRanges_2.38.0 S4Vectors_0.42.0

[21] BiocGenerics_0.50.0 MatrixGenerics_1.16.0

[23] matrixStats_1.3.0 BiocStyle_2.32.0

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] jsonlite_1.8.8 magrittr_2.0.3

[3] ggbeeswarm_0.7.2 magick_2.8.3

[5] farver_2.1.2 rmarkdown_2.27

[7] BiocIO_1.14.0 zlibbioc_1.50.0

[9] vctrs_0.6.5 memoise_2.0.1

[11] Rsamtools_2.20.0 DelayedMatrixStats_1.26.0

[13] RCurl_1.98-1.14 htmltools_0.5.8.1

[15] S4Arrays_1.4.1 AnnotationHub_3.12.0

[17] curl_5.2.1 BiocNeighbors_1.22.0

[19] xgboost_1.7.7.1 Rhdf5lib_1.26.0

[21] SparseArray_1.4.8 rhdf5_2.48.0

[23] cachem_1.1.0 GenomicAlignments_1.40.0

[25] igraph_2.0.3 mime_0.12

[27] lifecycle_1.0.4 pkgconfig_2.0.3

[29] rsvd_1.0.5 Matrix_1.7-0

[31] R6_2.5.1 fastmap_1.2.0

[33] GenomeInfoDbData_1.2.12 digest_0.6.35

[35] colorspace_2.1-0 dqrng_0.4.1

[37] irlba_2.3.5.1 ExperimentHub_2.12.0

[39] RSQLite_2.3.7 beachmat_2.20.0

[41] labeling_0.4.3 filelock_1.0.3

[43] fansi_1.0.6 httr_1.4.7

[45] abind_1.4-5 compiler_4.4.1

[47] bit64_4.0.5 withr_3.0.0

[49] BiocParallel_1.38.0 viridis_0.6.5

[51] DBI_1.2.3 highr_0.11

[53] HDF5Array_1.32.0 R.utils_2.12.3

[55] MASS_7.3-60.2 rappdirs_0.3.3

[57] DelayedArray_0.30.1 bluster_1.14.0

[59] rjson_0.2.21 tools_4.4.1

[61] vipor_0.4.7 beeswarm_0.4.0

[63] R.oo_1.26.0 glue_1.7.0

[65] restfulr_0.0.15 rhdf5filters_1.16.0

[67] grid_4.4.1 Rtsne_0.17

[69] cluster_2.1.6 generics_0.1.3

[71] gtable_0.3.5 R.methodsS3_1.8.2

[73] data.table_1.15.4 metapod_1.12.0

[75] BiocSingular_1.20.0 ScaledMatrix_1.12.0

[77] utf8_1.2.4 XVector_0.44.0

[79] ggrepel_0.9.5 BiocVersion_3.19.1

[81] pillar_1.9.0 limma_3.60.2

[83] BumpyMatrix_1.12.0 dplyr_1.1.4

[85] BiocFileCache_2.12.0 lattice_0.22-6

[87] FNN_1.1.4 renv_1.0.11

[89] rtracklayer_1.64.0 bit_4.0.5

[91] tidyselect_1.2.1 locfit_1.5-9.9

[93] Biostrings_2.72.1 knitr_1.47

[95] gridExtra_2.3 ProtGenerics_1.36.0

[97] edgeR_4.2.0 xfun_0.44

[99] statmod_1.5.0 UCSC.utils_1.0.0

[101] lazyeval_0.2.2 yaml_2.3.8

[103] evaluate_0.23 codetools_0.2-20

[105] tibble_3.2.1 BiocManager_1.30.23

[107] cli_3.6.2 uwot_0.2.2

[109] munsell_0.5.1 Rcpp_1.0.12

[111] dbplyr_2.5.0 png_0.1-8

[113] XML_3.99-0.16.1 parallel_4.4.1

[115] blob_1.2.4 sparseMatrixStats_1.16.0

[117] bitops_1.0-7 viridisLite_0.4.2

[119] scales_1.3.0 purrr_1.0.2

[121] crayon_1.5.2 rlang_1.1.3

[123] formatR_1.14 cowplot_1.1.3

[125] KEGGREST_1.44.0