Working with large data

Last updated on 2024-11-11 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- How do we work with single-cell datasets that are too large to fit in memory?

- How do we speed up single-cell analysis workflows for large datasets?

- How do we convert between popular single-cell data formats?

Objectives

- Work with out-of-memory data representations such as HDF5.

- Speed up single-cell analysis with parallel computation.

- Invoke fast approximations for essential analysis steps.

- Convert

SingleCellExperimentobjects toSeuratObjects andAnnDataobjects.

Motivation

Advances in scRNA-seq technologies have increased the number of cells that can be assayed in routine experiments. Public databases such as GEO are continually expanding with more scRNA-seq studies, while large-scale projects such as the Human Cell Atlas are expected to generate data for billions of cells. For effective data analysis, the computational methods need to scale with the increasing size of scRNA-seq data sets. This section discusses how we can use various aspects of the Bioconductor ecosystem to tune our analysis pipelines for greater speed and efficiency.

Out of memory representations

The count matrix is the central structure around which our analyses

are based. In most of the previous chapters, this has been held fully in

memory as a dense matrix or as a sparse

dgCMatrix. Howevever, in-memory representations may not be

feasible for very large data sets, especially on machines with limited

memory. For example, the 1.3 million brain cell data set from 10X

Genomics (Zheng et al.,

2017) would require over 100 GB of RAM to hold as a

matrix and around 30 GB as a dgCMatrix. This

makes it challenging to explore the data on anything less than a HPC

system.

The obvious solution is to use a file-backed matrix representation where the data are held on disk and subsets are retrieved into memory as requested. While a number of implementations of file-backed matrices are available (e.g., bigmemory, matter), we will be using the implementation from the HDF5Array package. This uses the popular HDF5 format as the underlying data store, which provides a measure of standardization and portability across systems. We demonstrate with a subset of 20,000 cells from the 1.3 million brain cell data set, as provided by the TENxBrainData package.

R

library(TENxBrainData)

sce.brain <- TENxBrainData20k()

sce.brain

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 27998 20000

metadata(0):

assays(1): counts

rownames: NULL

rowData names(2): Ensembl Symbol

colnames: NULL

colData names(4): Barcode Sequence Library Mouse

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):Examination of the SingleCellExperiment object indicates

that the count matrix is a HDF5Matrix. From a comparison of

the memory usage, it is clear that this matrix object is simply a stub

that points to the much larger HDF5 file that actually contains the

data. This avoids the need for large RAM availability during

analyses.

R

counts(sce.brain)

OUTPUT

<27998 x 20000> HDF5Matrix object of type "integer":

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] ... [,19997] [,19998] [,19999]

[1,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[2,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[3,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[4,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[5,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

... . . . . . . . .

[27994,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[27995,] 0 0 0 1 . 0 2 0

[27996,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 1 0

[27997,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[27998,] 0 0 0 0 . 0 0 0

[,20000]

[1,] 0

[2,] 0

[3,] 0

[4,] 0

[5,] 0

... .

[27994,] 0

[27995,] 0

[27996,] 0

[27997,] 0

[27998,] 0R

object.size(counts(sce.brain))

OUTPUT

2496 bytesR

file.info(path(counts(sce.brain)))$size

OUTPUT

[1] 76264332Manipulation of the count matrix will generally result in the

creation of a DelayedArray object from the DelayedArray

package. This remembers the operations to be applied to the counts and

stores them in the object, to be executed when the modified matrix

values are realized for use in calculations. The use of delayed

operations avoids the need to write the modified values to a new file at

every operation, which would unnecessarily require time-consuming disk

I/O.

R

tmp <- counts(sce.brain)

tmp <- log2(tmp + 1)

tmp

OUTPUT

<27998 x 20000> DelayedMatrix object of type "double":

[,1] [,2] [,3] ... [,19999] [,20000]

[1,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[2,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[3,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[4,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[5,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

... . . . . . .

[27994,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[27995,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[27996,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[27997,] 0 0 0 . 0 0

[27998,] 0 0 0 . 0 0Many functions described in the previous workflows are capable of

accepting HDF5Matrix objects. This is powered by the

availability of common methods for all matrix representations (e.g.,

subsetting, combining, methods from DelayedMatrixStats

as well as representation-agnostic C++ code using beachmat. For

example, we compute QC metrics below with the same

calculateQCMetrics() function that we used in the other

workflows.

R

library(scater)

is.mito <- grepl("^mt-", rowData(sce.brain)$Symbol)

qcstats <- perCellQCMetrics(sce.brain, subsets = list(Mt = is.mito))

qcstats

OUTPUT

DataFrame with 20000 rows and 6 columns

sum detected subsets_Mt_sum subsets_Mt_detected subsets_Mt_percent

<numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric>

1 3060 1546 123 10 4.01961

2 3500 1694 118 11 3.37143

3 3092 1613 58 9 1.87581

4 4420 2050 131 10 2.96380

5 3771 1813 100 8 2.65182

... ... ... ... ... ...

19996 4431 2050 127 9 2.866170

19997 6988 2704 60 9 0.858615

19998 8749 2988 305 11 3.486113

19999 3842 1711 129 8 3.357626

20000 1775 945 26 6 1.464789

total

<numeric>

1 3060

2 3500

3 3092

4 4420

5 3771

... ...

19996 4431

19997 6988

19998 8749

19999 3842

20000 1775Needless to say, data access from file-backed representations is slower than that from in-memory representations. The time spent retrieving data from disk is an unavoidable cost of reducing memory usage. Whether this is tolerable depends on the application. One example usage pattern involves performing the heavy computing quickly with in-memory representations on HPC systems with plentiful memory, and then distributing file-backed counterparts to individual users for exploration and visualization on their personal machines.

Parallelization

Parallelization of calculations across genes or cells is an obvious strategy for speeding up scRNA-seq analysis workflows.

The BiocParallel

package provides a common interface for parallel computing throughout

the Bioconductor ecosystem, manifesting as a BPPARAM

argument in compatible functions. We can also use

BiocParallel with more expressive functions directly

through the package’s interface.

Basic use

R

library(BiocParallel)

BiocParallel makes it quite easy to iterate over a

vector and distribute the computation across workers using the

bplapply function. Basic knowledge of lapply

is required.

In this example, we find the square root of a vector of numbers in

parallel by indicating the BPPARAM argument in

bplapply.

R

param <- MulticoreParam(workers = 1)

bplapply(

X = c(4, 9, 16, 25),

FUN = sqrt,

BPPARAM = param

)

OUTPUT

[[1]]

[1] 2

[[2]]

[1] 3

[[3]]

[1] 4

[[4]]

[1] 5Note. The number of workers is set to 1 due to continuous testing resource limitations.

There exists a diverse set of parallelization backends depending on available hardware and operating systems.

For example, we might use forking across two cores to parallelize the variance calculations on a Unix system:

R

library(MouseGastrulationData)

library(scran)

sce <- WTChimeraData(samples = 5, type = "processed")

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

dec.mc <- modelGeneVar(sce, BPPARAM = MulticoreParam(2))

dec.mc

OUTPUT

DataFrame with 29453 rows and 6 columns

mean total tech bio p.value

<numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric> <numeric>

ENSMUSG00000051951 0.002800256 0.003504940 0.002856697 6.48243e-04 1.20905e-01

ENSMUSG00000089699 0.000000000 0.000000000 0.000000000 0.00000e+00 NaN

ENSMUSG00000102343 0.000000000 0.000000000 0.000000000 0.00000e+00 NaN

ENSMUSG00000025900 0.000794995 0.000863633 0.000811019 5.26143e-05 3.68953e-01

ENSMUSG00000025902 0.170777718 0.388633677 0.170891603 2.17742e-01 2.47893e-11

... ... ... ... ... ...

ENSMUSG00000095041 0.35571083 0.34572194 0.33640994 0.00931199 0.443233

ENSMUSG00000063897 0.49007956 0.41924282 0.44078158 -0.02153876 0.599499

ENSMUSG00000096730 0.00000000 0.00000000 0.00000000 0.00000000 NaN

ENSMUSG00000095742 0.00177158 0.00211619 0.00180729 0.00030890 0.188992

tomato-td 0.57257331 0.47487832 0.49719425 -0.02231593 0.591542

FDR

<numeric>

ENSMUSG00000051951 6.76255e-01

ENSMUSG00000089699 NaN

ENSMUSG00000102343 NaN

ENSMUSG00000025900 7.56202e-01

ENSMUSG00000025902 1.35508e-09

... ...

ENSMUSG00000095041 0.756202

ENSMUSG00000063897 0.756202

ENSMUSG00000096730 NaN

ENSMUSG00000095742 0.756202

tomato-td 0.756202Another approach would be to distribute jobs across a network of computers, which yields the same result:

R

dec.snow <- modelGeneVar(sce, BPPARAM = SnowParam(2))

For high-performance computing (HPC) systems with a cluster of

compute nodes, we can distribute jobs via the job scheduler using the

BatchtoolsParam class. The example below assumes a SLURM

cluster, though the settings can be easily configured for a particular

system (see here

for details).

R

# 2 hours, 8 GB, 1 CPU per task, for 10 tasks.

rs <- list(walltime = 7200, memory = 8000, ncpus = 1)

bpp <- BatchtoolsParam(10, cluster = "slurm", resources = rs)

Parallelization is best suited for independent, CPU-intensive tasks where the division of labor results in a concomitant reduction in compute time. It is not suited for tasks that are bounded by other compute resources, e.g., memory or file I/O (though the latter is less of an issue on HPC systems with parallel read/write). In particular, R itself is inherently single-core, so many of the parallelization backends involve (i) setting up one or more separate R sessions, (ii) loading the relevant packages and (iii) transmitting the data to that session. Depending on the nature and size of the task, this overhead may outweigh any benefit from parallel computing. While the default behavior of the parallel job managers often works well for simple cases, it is sometimes necessary to explicitly specify what data/libraries are sent to / loaded on the parallel workers in order to avoid unnecessary overhead.

Challenge

How do you turn on progress bars with parallel processing?

From ?MulticoreParam :

progressbarlogical(1) Enable progress bar (based on plyr:::progress_text). Enabling the progress bar changes the default value of tasks to .Machine$integer.max, so that progress is reported for each element of X.

Progress bars are a helpful way to gauge whether that task is going to take 5 minutes or 5 hours.

Fast approximations

Nearest neighbor searching

Identification of neighbouring cells in PC or expression space is a

common procedure that is used in many functions, e.g.,

buildSNNGraph(), doubletCells(). The default

is to favour accuracy over speed by using an exact nearest neighbour

(NN) search, implemented with the \(k\)-means for \(k\)-nearest neighbours algorithm. However,

for large data sets, it may be preferable to use a faster approximate

approach.

The BiocNeighbors

framework makes it easy to switch between search options by simply

changing the BNPARAM argument in compatible functions. To

demonstrate, we will use the wild-type chimera data for which we had

applied graph-based clustering using the Louvain algorithm for community

detection:

R

library(bluster)

sce <- runPCA(sce)

colLabels(sce) <- clusterCells(sce, use.dimred = "PCA",

BLUSPARAM = NNGraphParam(cluster.fun = "louvain"))

The above clusters on a nearest neighbor graph generated with an

exact neighbour search. We repeat this below using an approximate

search, implemented using the Annoy algorithm. This

involves constructing a AnnoyParam object to specify the

search algorithm and then passing it to the parameterization of the

NNGraphParam() function. The results from the exact and

approximate searches are consistent with most clusters from the former

re-appearing in the latter. This suggests that the inaccuracy from the

approximation can be largely ignored.

R

library(scran)

library(BiocNeighbors)

clusters <- clusterCells(sce, use.dimred = "PCA",

BLUSPARAM = NNGraphParam(cluster.fun = "louvain",

BNPARAM = AnnoyParam()))

table(exact = colLabels(sce), approx = clusters)

OUTPUT

approx

exact 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15

1 91 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

2 0 143 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1

3 0 0 75 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

4 0 0 0 341 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 56

5 0 0 2 0 74 0 0 0 0 0 0 320 0 0 0

6 0 0 0 0 0 81 246 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0

7 0 0 0 0 0 128 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

8 0 0 0 0 95 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

9 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 108 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 113 0 0 0 0 0 0

11 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 7 139 0 0 6 0 0

12 0 0 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 205 1 0 0 0

13 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 143 0 1

14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 20 0The similarity of the two clusterings can be quantified by calculating the pairwise Rand index:

R

rand <- pairwiseRand(colLabels(sce), clusters, mode = "index")

stopifnot(rand > 0.8)

Note that Annoy writes the NN index to disk prior to performing the search. Thus, it may not actually be faster than the default exact algorithm for small datasets, depending on whether the overhead of disk write is offset by the computational complexity of the search. It is also not difficult to find situations where the approximation deteriorates, especially at high dimensions, though this may not have an appreciable impact on the biological conclusions.

R

set.seed(1000)

y1 <- matrix(rnorm(50000), nrow = 1000)

y2 <- matrix(rnorm(50000), nrow = 1000)

Y <- rbind(y1, y2)

exact <- findKNN(Y, k = 20)

approx <- findKNN(Y, k = 20, BNPARAM = AnnoyParam())

mean(exact$index != approx$index)

OUTPUT

[1] 0.561925Singular value decomposition

The singular value decomposition (SVD) underlies the PCA used

throughout our analyses, e.g., in denoisePCA(),

fastMNN(), doubletCells(). (Briefly, the right

singular vectors are the eigenvectors of the gene-gene covariance

matrix, where each eigenvector represents the axis of maximum remaining

variation in the PCA.) The default base::svd() function

performs an exact SVD that is not performant for large datasets.

Instead, we use fast approximate methods from the irlba and

rsvd

packages, conveniently wrapped into the BiocSingular

package for ease of use and package development. Specifically, we can

change the SVD algorithm used in any of these functions by simply

specifying an alternative value for the BSPARAM

argument.

R

library(scater)

library(BiocSingular)

# As the name suggests, it is random, so we need to set the seed.

set.seed(101000)

r.out <- runPCA(sce, ncomponents = 20, BSPARAM = RandomParam())

str(reducedDim(r.out, "PCA"))

OUTPUT

num [1:2411, 1:20] 14.79 5.79 13.07 -32.19 -26.45 ...

- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

..$ : chr [1:2411] "cell_9769" "cell_9770" "cell_9771" "cell_9772" ...

..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...

- attr(*, "varExplained")= num [1:20] 192.6 87 29.4 23.1 21.6 ...

- attr(*, "percentVar")= num [1:20] 25.84 11.67 3.94 3.1 2.89 ...

- attr(*, "rotation")= num [1:500, 1:20] -0.174 -0.173 -0.157 0.105 -0.132 ...

..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

.. ..$ : chr [1:500] "ENSMUSG00000055609" "ENSMUSG00000052217" "ENSMUSG00000069919" "ENSMUSG00000048583" ...

.. ..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...R

set.seed(101001)

i.out <- runPCA(sce, ncomponents = 20, BSPARAM = IrlbaParam())

str(reducedDim(i.out, "PCA"))

OUTPUT

num [1:2411, 1:20] -14.79 -5.79 -13.07 32.19 26.45 ...

- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

..$ : chr [1:2411] "cell_9769" "cell_9770" "cell_9771" "cell_9772" ...

..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...

- attr(*, "varExplained")= num [1:20] 192.6 87 29.4 23.1 21.6 ...

- attr(*, "percentVar")= num [1:20] 25.84 11.67 3.94 3.1 2.89 ...

- attr(*, "rotation")= num [1:500, 1:20] 0.174 0.173 0.157 -0.105 0.132 ...

..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

.. ..$ : chr [1:500] "ENSMUSG00000055609" "ENSMUSG00000052217" "ENSMUSG00000069919" "ENSMUSG00000048583" ...

.. ..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...Both IRLBA and randomized SVD (RSVD) are much faster than the exact

SVD and usually yield only a negligible loss of accuracy. This motivates

their default use in many scran and

scater

functions, at the cost of requiring users to set the seed to guarantee

reproducibility. IRLBA can occasionally fail to converge and require

more iterations (passed via maxit= in

IrlbaParam()), while RSVD involves an explicit trade-off

between accuracy and speed based on its oversampling parameter

(p=) and number of power iterations (q=). We

tend to prefer IRLBA as its default behavior is more accurate, though

RSVD is much faster for file-backed matrices.

Challenge

The uncertainty from approximation error is sometimes aggravating.

“Why can’t my computer just give me the right answer?” One way to

alleviate this feeling is to quantify the approximation error on a small

test set like the sce we have here. Using the ExactParam()

class, visualize the error in PC1 coordinates compared to the RSVD

results.

This code block calculates the exact PCA coordinates. Another thing to note: PC vectors are only identified up to a sign flip. We can see that the RSVD PC1 vector points in the

R

set.seed(123)

e.out <- runPCA(sce, ncomponents = 20, BSPARAM = ExactParam())

str(reducedDim(e.out, "PCA"))

OUTPUT

num [1:2411, 1:20] -14.79 -5.79 -13.07 32.19 26.45 ...

- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

..$ : chr [1:2411] "cell_9769" "cell_9770" "cell_9771" "cell_9772" ...

..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...

- attr(*, "varExplained")= num [1:20] 192.6 87 29.4 23.1 21.6 ...

- attr(*, "percentVar")= num [1:20] 25.84 11.67 3.94 3.1 2.89 ...

- attr(*, "rotation")= num [1:500, 1:20] 0.174 0.173 0.157 -0.105 0.132 ...

..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2

.. ..$ : chr [1:500] "ENSMUSG00000055609" "ENSMUSG00000052217" "ENSMUSG00000069919" "ENSMUSG00000048583" ...

.. ..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ...R

reducedDim(e.out, "PCA")[1:5,1:3]

OUTPUT

PC1 PC2 PC3

cell_9769 -14.793684 18.470324 -0.4893474

cell_9770 -5.789032 13.347277 5.0560761

cell_9771 -13.066503 16.803152 -0.5602737

cell_9772 32.185950 6.697517 -0.6945423

cell_9773 26.452390 3.083474 -0.2271916R

reducedDim(r.out, "PCA")[1:5,1:3]

OUTPUT

PC1 PC2 PC3

cell_9769 14.793780 18.470111 -0.4888676

cell_9770 5.789148 13.348438 5.0702153

cell_9771 13.066327 16.803423 -0.5562241

cell_9772 -32.186341 6.698347 -0.6892421

cell_9773 -26.452373 3.083974 -0.2299814For the sake of visualizing the error we can just flip the PC1 coordinates:

R

reducedDim(r.out, "PCA") = -1 * reducedDim(r.out, "PCA")

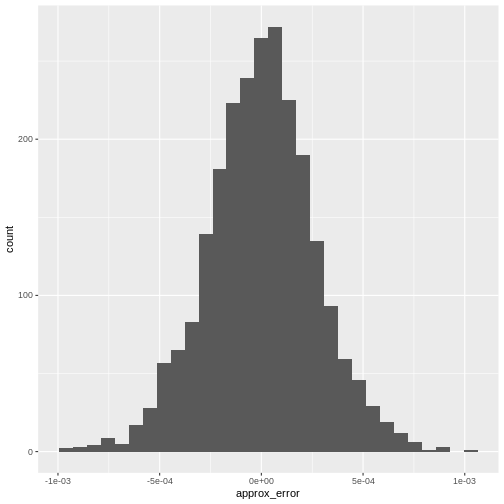

From there we can visualize the error with a histogram:

R

error <- reducedDim(r.out, "PCA")[,"PC1"] -

reducedDim(e.out, "PCA")[,"PC1"]

data.frame(approx_error = error) |>

ggplot(aes(approx_error)) +

geom_histogram()

It’s almost never more than .001 in this case.

Interoperability with popular single-cell analysis ecosytems

Seurat

Seurat is an R package designed for QC, analysis, and exploration of single-cell RNA-seq data. Seurat can be used to identify and interpret sources of heterogeneity from single-cell transcriptomic measurements, and to integrate diverse types of single-cell data. Seurat is developed and maintained by the Satija lab and is released under the MIT license.

R

library(Seurat)

Although the basic processing of single-cell data with Bioconductor

packages (described in the OSCA book) and

with Seurat is very similar and will produce overall roughly identical

results, there is also complementary functionality with regard to cell

type annotation, dataset integration, and downstream analysis. To make

the most of both ecosystems it is therefore beneficial to be able to

easily switch between a SeuratObject and a

SingleCellExperiment. See also the Seurat conversion

vignette for conversion to/from other popular single cell formats

such as the AnnData format used by scanpy.

Here, we demonstrate converting the Seurat object produced in

Seurat’s PBMC

tutorial to a SingleCellExperiment for further analysis

with functionality from OSCA/Bioconductor. We therefore need to first

install the SeuratData package,

which is available from GitHub only.

R

BiocManager::install("satijalab/seurat-data")

We then proceed by loading all required packages and installing the PBMC dataset:

R

library(SeuratData)

InstallData("pbmc3k")

We then load the dataset as an SeuratObject and convert

it to a SingleCellExperiment.

R

# Use PBMC3K from SeuratData

pbmc <- LoadData(ds = "pbmc3k", type = "pbmc3k.final")

pbmc <- UpdateSeuratObject(pbmc)

pbmc

pbmc.sce <- as.SingleCellExperiment(pbmc)

pbmc.sce

Seurat also allows conversion from SingleCellExperiment

objects to Seurat objects; we demonstrate this here on the wild-type

chimera mouse gastrulation dataset.

R

sce <- WTChimeraData(samples = 5, type = "processed")

assay(sce) <- as.matrix(assay(sce))

sce <- logNormCounts(sce)

sce

After some processing of the dataset, the actual conversion is

carried out with the as.Seurat function.

R

sobj <- as.Seurat(sce)

Idents(sobj) <- "celltype.mapped"

sobj

Scanpy

Scanpy is a scalable toolkit for analyzing single-cell gene expression data built jointly with anndata. It includes preprocessing, visualization, clustering, trajectory inference and differential expression testing. The Python-based implementation efficiently deals with datasets of more than one million cells. Scanpy is developed and maintained by the Theis lab and is released under a BSD-3-Clause license. Scanpy is part of the scverse, a Python-based ecosystem for single-cell omics data analysis.

At the core of scanpy’s single-cell functionality is the

anndata data structure, scanpy’s integrated single-cell

data container, which is conceptually very similar to Bioconductor’s

SingleCellExperiment class.

Bioconductor’s zellkonverter

package provides a lightweight interface between the Bioconductor

SingleCellExperiment data structure and the Python

AnnData-based single-cell analysis environment. The idea is

to enable users and developers to easily move data between these

frameworks to construct a multi-language analysis pipeline across

R/Bioconductor and Python.

R

library(zellkonverter)

The readH5AD() function can be used to read a

SingleCellExperiment from an H5AD file. Here, we use an

example H5AD file contained in the zellkonverter

package.

R

example_h5ad <- system.file("extdata", "krumsiek11.h5ad",

package = "zellkonverter")

readH5AD(example_h5ad)

OUTPUT

class: SingleCellExperiment

dim: 11 640

metadata(2): highlights iroot

assays(1): X

rownames(11): Gata2 Gata1 ... EgrNab Gfi1

rowData names(0):

colnames(640): 0 1 ... 158-3 159-3

colData names(1): cell_type

reducedDimNames(0):

mainExpName: NULL

altExpNames(0):We can also write a SingleCellExperiment to an H5AD file

with the writeH5AD() function. This is demonstrated below

on the wild-type chimera mouse gastrulation dataset.

R

out.file <- tempfile(fileext = ".h5ad")

writeH5AD(sce, file = out.file)

The resulting H5AD file can then be read into Python using scanpy’s read_h5ad function and then directly used in compatible Python-based analysis frameworks.

Exercises

Exercise 1: Out of memory representation

Write the counts matrix of the wild-type chimera mouse gastrulation dataset to an HDF5 file. Create another counts matrix that reads the data from the HDF5 file. Compare memory usage of holding the entire matrix in memory as opposed to holding the data out of memory.

See the HDF5Array function for reading from HDF5 and the

writeHDF5Array function for writing to HDF5 from the HDF5Array

package.

R

wt_out <- tempfile(fileext = ".h5")

wt_counts <- counts(WTChimeraData())

writeHDF5Array(wt_counts,

name = "wt_counts",

file = wt_out)

OUTPUT

<29453 x 30703> sparse HDF5Matrix object of type "double":

cell_1 cell_2 cell_3 ... cell_30702 cell_30703

ENSMUSG00000051951 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000089699 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000102343 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000025900 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000025902 0 0 0 . 0 0

... . . . . . .

ENSMUSG00000095041 0 1 2 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000063897 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000096730 0 0 0 . 0 0

ENSMUSG00000095742 0 0 0 . 0 0

tomato-td 1 0 1 . 0 0R

oom_wt <- HDF5Array(wt_out, "wt_counts")

object.size(wt_counts)

OUTPUT

1520366960 bytesR

object.size(oom_wt)

OUTPUT

2488 bytesExercise 2: Parallelization

Perform a PCA analysis of the wild-type chimera mouse gastrulation dataset using a multicore backend for parallel computation. Compare the runtime of performing the PCA either in serial execution mode, in multicore execution mode with 2 workers, and in multicore execution mode with 3 workers.

Use the function system.time to obtain the runtime of

each job.

R

sce.brain <- logNormCounts(sce.brain)

system.time({i.out <- runPCA(sce.brain,

ncomponents = 20,

BSPARAM = ExactParam(),

BPPARAM = SerialParam())})

system.time({i.out <- runPCA(sce.brain,

ncomponents = 20,

BSPARAM = ExactParam(),

BPPARAM = MulticoreParam(workers = 2))})

system.time({i.out <- runPCA(sce.brain,

ncomponents = 20,

BSPARAM = ExactParam(),

BPPARAM = MulticoreParam(workers = 3))})

Further Reading

- OSCA book, Chapter 14: Dealing with big data

- The

BiocParallelintro vignette.

Key Points

- Out-of-memory representations can be used to work with single-cell datasets that are too large to fit in memory.

- Parallelization of calculations across genes or cells is an effective strategy for speeding up analysis of large single-cell datasets.

- Fast approximations for nearest neighbor search and singular value composition can speed up essential steps of single-cell analysis with minimal loss of accuracy.

- Converter functions between existing single-cell data formats enable analysis workflows that leverage complementary functionality from poplular single-cell analysis ecosystems.

Session Info

R

sessionInfo()

OUTPUT

R version 4.4.1 (2024-06-14)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/blas/libblas.so.3.10.0

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/lapack/liblapack.so.3.10.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

[4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

[10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats4 stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods

[8] base

other attached packages:

[1] zellkonverter_1.14.0 Seurat_5.1.0

[3] SeuratObject_5.0.2 sp_2.1-4

[5] BiocSingular_1.20.0 BiocNeighbors_1.22.0

[7] bluster_1.14.0 scran_1.32.0

[9] MouseGastrulationData_1.18.0 SpatialExperiment_1.14.0

[11] BiocParallel_1.38.0 scater_1.32.0

[13] ggplot2_3.5.1 scuttle_1.14.0

[15] TENxBrainData_1.24.0 HDF5Array_1.32.0

[17] rhdf5_2.48.0 DelayedArray_0.30.1

[19] SparseArray_1.4.8 S4Arrays_1.4.1

[21] abind_1.4-5 Matrix_1.7-0

[23] SingleCellExperiment_1.26.0 SummarizedExperiment_1.34.0

[25] Biobase_2.64.0 GenomicRanges_1.56.0

[27] GenomeInfoDb_1.40.1 IRanges_2.38.0

[29] S4Vectors_0.42.0 BiocGenerics_0.50.0

[31] MatrixGenerics_1.16.0 matrixStats_1.3.0

[33] BiocStyle_2.32.0

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] spatstat.sparse_3.0-3 httr_1.4.7

[3] RColorBrewer_1.1-3 tools_4.4.1

[5] sctransform_0.4.1 utf8_1.2.4

[7] R6_2.5.1 lazyeval_0.2.2

[9] uwot_0.2.2 rhdf5filters_1.16.0

[11] withr_3.0.0 gridExtra_2.3

[13] progressr_0.14.0 cli_3.6.2

[15] formatR_1.14 spatstat.explore_3.2-7

[17] fastDummies_1.7.3 labeling_0.4.3

[19] spatstat.data_3.0-4 ggridges_0.5.6

[21] pbapply_1.7-2 parallelly_1.37.1

[23] limma_3.60.2 RSQLite_2.3.7

[25] generics_0.1.3 ica_1.0-3

[27] spatstat.random_3.2-3 dplyr_1.1.4

[29] ggbeeswarm_0.7.2 fansi_1.0.6

[31] lifecycle_1.0.4 yaml_2.3.8

[33] edgeR_4.2.0 BiocFileCache_2.12.0

[35] Rtsne_0.17 grid_4.4.1

[37] blob_1.2.4 promises_1.3.0

[39] dqrng_0.4.1 ExperimentHub_2.12.0

[41] crayon_1.5.2 dir.expiry_1.12.0

[43] miniUI_0.1.1.1 lattice_0.22-6

[45] beachmat_2.20.0 cowplot_1.1.3

[47] KEGGREST_1.44.0 magick_2.8.3

[49] pillar_1.9.0 knitr_1.47

[51] metapod_1.12.0 rjson_0.2.21

[53] future.apply_1.11.2 codetools_0.2-20

[55] leiden_0.4.3.1 glue_1.7.0

[57] data.table_1.15.4 vctrs_0.6.5

[59] png_0.1-8 spam_2.10-0

[61] gtable_0.3.5 cachem_1.1.0

[63] xfun_0.44 mime_0.12

[65] survival_3.6-4 statmod_1.5.0

[67] fitdistrplus_1.1-11 ROCR_1.0-11

[69] nlme_3.1-164 bit64_4.0.5

[71] filelock_1.0.3 RcppAnnoy_0.0.22

[73] BumpyMatrix_1.12.0 irlba_2.3.5.1

[75] vipor_0.4.7 KernSmooth_2.23-24

[77] colorspace_2.1-0 DBI_1.2.3

[79] tidyselect_1.2.1 bit_4.0.5

[81] compiler_4.4.1 curl_5.2.1

[83] basilisk.utils_1.16.0 plotly_4.10.4

[85] scales_1.3.0 lmtest_0.9-40

[87] rappdirs_0.3.3 stringr_1.5.1

[89] digest_0.6.35 goftest_1.2-3

[91] spatstat.utils_3.0-4 rmarkdown_2.27

[93] basilisk_1.16.0 XVector_0.44.0

[95] htmltools_0.5.8.1 pkgconfig_2.0.3

[97] sparseMatrixStats_1.16.0 highr_0.11

[99] dbplyr_2.5.0 fastmap_1.2.0

[101] rlang_1.1.3 htmlwidgets_1.6.4

[103] UCSC.utils_1.0.0 shiny_1.8.1.1

[105] DelayedMatrixStats_1.26.0 farver_2.1.2

[107] zoo_1.8-12 jsonlite_1.8.8

[109] magrittr_2.0.3 GenomeInfoDbData_1.2.12

[111] dotCall64_1.1-1 patchwork_1.2.0

[113] Rhdf5lib_1.26.0 munsell_0.5.1

[115] Rcpp_1.0.12 viridis_0.6.5

[117] reticulate_1.37.0 stringi_1.8.4

[119] zlibbioc_1.50.0 MASS_7.3-60.2

[121] AnnotationHub_3.12.0 plyr_1.8.9

[123] parallel_4.4.1 listenv_0.9.1

[125] ggrepel_0.9.5 deldir_2.0-4

[127] Biostrings_2.72.1 splines_4.4.1

[129] tensor_1.5 locfit_1.5-9.9

[131] igraph_2.0.3 spatstat.geom_3.2-9

[133] RcppHNSW_0.6.0 reshape2_1.4.4

[135] ScaledMatrix_1.12.0 BiocVersion_3.19.1

[137] evaluate_0.23 renv_1.0.11

[139] BiocManager_1.30.23 httpuv_1.6.15

[141] RANN_2.6.1 tidyr_1.3.1

[143] purrr_1.0.2 polyclip_1.10-6

[145] future_1.33.2 scattermore_1.2

[147] rsvd_1.0.5 xtable_1.8-4

[149] RSpectra_0.16-1 later_1.3.2

[151] viridisLite_0.4.2 tibble_3.2.1

[153] memoise_2.0.1 beeswarm_0.4.0

[155] AnnotationDbi_1.66.0 cluster_2.1.6

[157] globals_0.16.3